1 day ago

By Michael Sheils McNameeBBC News

ParamountAndroid character Data describes the “Irish unification of 2024” as a successful example of violence used to achieve political aims

ParamountAndroid character Data describes the “Irish unification of 2024” as a successful example of violence used to achieve political aims

When sci-fi writer Melinda M Snodgrass sat down to write Star Trek episode The High Ground, she had little idea of the unexpected ripples of controversy it would still be making more than three decades later.

“We became aware of it later… and there isn’t much you can do about it,” she says, speaking to the BBC from her home in New Mexico. “Writing for television is like laying track for a train that’s about 300 feet behind you. You really don’t have time to stop.”

While the series has legions of followers steeped in its lore, that one particular episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation has lived long and prospered in infamy.

It comes down to a scene in which the android character Data, played by actor Brent Spiner, talks about the “Irish unification of 2024” as an example of violence successfully achieving a political aim.

Originally shown in the US in 1990, there was so much concern over the exchange that the episode was not broadcast on the BBC or Irish public broadcaster RTÉ.

At the time, US TV shows often debuted internationally several years after their original broadcast.

Satellite broadcaster Sky reportedly aired an edited version in 1992, cutting the crucial scene. But The High Ground was not shown by the BBC until 02:39 GMT, 29 September 2007 – and BBC Archives says it is confident this is its only transmission.

The decision not to air the episode reflects a time when a bloody conflict continued to rage in Northern Ireland, with the Provisional IRA – a paramilitary group with the stated aim of ending British rule in Northern Ireland – one of its main protagonists.

Now it is 2024 – and Sinn Féin, which emerged as the political wing of the IRA, is the largest party in the devolved Stormont assembly.

The party’s leader in Northern Ireland, Michelle O’Neill, became first minister last month and has predicted a referendum on Irish unity within a decade.

She strikes a very different tone to Sir Keir Starmer, favourite to be the UK’s next prime minister, who has said such a poll is “not even on the horizon”.Michelle O’Neill became Northern Ireland’s first minister last month, the first time a Irish nationalist politician has held that role

On social media, people have been sharing screenshots of Data’s prediction and drawing links to Sinn Féin’s electoral success.

Back when Ms Snodgrass was writing the script, she did not think it would cause any problems. “Science fiction is incredibly important because it allows people to discuss difficult topics – but at arm’s length,” she says.

In the episode, Data’s line does not come out of the blue.

The High Ground is based on the theme of terrorism, after the Starship Enterprise’s chief medical officer Dr Beverly Crusher is abducted by the separatist Ansata group, who use murder and violence to pursue their aim of independence.

“I’ve been reviewing the history of armed rebellion, and it appears that terrorism is an effective way to promote political change,” says Data.

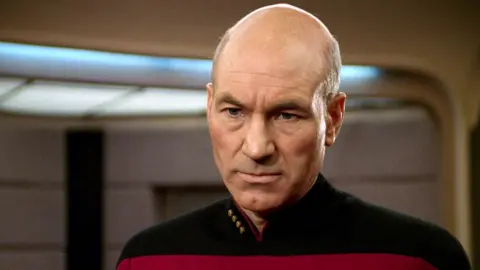

“Yes it can be,” responds Captain Jean-Luc Picard, played by Patrick Stewart, “but I have never subscribed to the theory that political power flows from the barrel of a gun.”

“Yet there are numerous examples of when it was successful,” Data says. “The independence of the Mexican state from Spain, the Irish unification of 2024, and the Kenzie rebellion.”

Getty ImagesStar Trek: The Next Generation featured Sir Patrick Stewart as Captain Jean-Luc Picard, in what has become one of his most iconic roles

Getty ImagesStar Trek: The Next Generation featured Sir Patrick Stewart as Captain Jean-Luc Picard, in what has become one of his most iconic roles

“I’m aware of them,” says Picard, to which Data asks: “Would it then be accurate to say that terrorism is acceptable when all options for peaceful settlement have been foreclosed?”

“Data, these are questions that mankind has been struggling with throughout history. Your confusion is only human.”

The story has parallels with the situation in Northern Ireland at the time – something Ms Snodgrass says was deliberate.

“I was a history major before I went to law school and I wanted to get into that; discuss the fact that one man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist,” she says.

“I mean, these are complicated issues. And when do people feel like their back is so much against the wall that they have no choice but to turn to violence? And is that actually ever justified?

“I think what I wanted to say was: if we’re talking and not shooting, we’re in a better place.”

Melinda M Snodgrass says science fiction provides a way of examining current issues through a different lens

In 1992, when the episode was due to air in the UK, the IRA ceasefire of 1994 and 1998 Good Friday Agreement were still years away.

In April of that year, the Baltic Exchange bombing carried out by the IRA in the heart of London’s financial centre killed three people, and injured more than 90.

Such was the atmosphere from 1988 to 1994, a ban was enforced on broadcasting the voices of members of certain groups from Northern Ireland on television and radio. Restrictions were seen as specifically targeting Sinn Féin.

It resulted in the bizarre situation where prominent politicians including Martin McGuinness and Gerry Adams had their voices dubbed by actors (Mr Adams, famously, was voiced at times by Oscar-nominated actor Stephen Rea).

Reflecting on the Star Trek episode, Prof Robert Savage of Boston College says: “It was amazing it was censored.”

His latest book – Northern Ireland, the BBC, and Censorship in Thatcher’s Britain – covers the period when the episode was pulled.

“The argument I think the robot [Data] asks you is basically just: does terrorism work? If there are no alternatives, if you’ve tried every other avenue to try to affect change, is it acceptable? To use terrorism?

“And it’s a very human question. But [Jean-Luc Picard] doesn’t answer the question! That would have unsettled somebody like Thatcher,” Prof Savage adds.The roots of Northern Ireland’s Troubles lie deep in Irish history

There is some murkiness about how a decision was reached not to broadcast the programme at the time.

BBC Archives confirmed the 2007 broadcast of the episode and was “satisfied” any other screening would have been listed.

The BBC’s press office said it had spoken to “a number of people” about why a ban may have been implemented, but was unable to get this information “as it dates quite far back”.

A spokesman for Sky said he had looked into it, but could not confirm it had broadcast an edited version of the episode in 1992 – or what its reasoning might have been for doing so.

RTÉ noted that TV guides from the time show it had broadcast Star Trek: The Next Generation, but did not have further information in its acquisitions system, and could not find anyone from the time to speak to.

“I think this would probably have stirred a memory if I had been made aware of this at the time, but I am afraid it rings no bells at all,” said Lord John Birt, who was director general of the BBC from 1992 to 2000, and before this served as deputy director general.

If the episode had been removed, it would probably have been a decision made at operational level in Network Television, he said.

More than three decades on, the picture in Northern Ireland has changed.

Ms Snodgrass says she was “thrilled” when the Good Friday Agreement was signed, adding it had allowed Northern Ireland to prosper.

She notes Games of Thrones, a television series based on books by George RR Martin (who she knows well and has co-authored work with) was filmed in the region in recent years – something which has given a big boost to the economy.

D/C: 1984 seemed a long way off too!!

In one 1948 letter, Orwell claims to have “first thought of [the book] in 1943”, while in another he says he thought of it in 1944 and cites 1943’s Tehran Conference as inspiration: “What it is really meant to do is to discuss the implications of dividing the world up into ‘Zones of Influence’ (I thought of it in 1944 as a result of the Tehran Conference), and in addition to indicate by parodying them the intellectual implications of totalitarianism”.[Orwell had toured Austria in May 1945 and observed manoeuvering he thought would likely lead to separate Soviet and Allied Zones of Occupation.

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka]) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943. It was held at the Soviet Union’s embassy at Tehran in Iran. It was the first of the World War II conferences of the “Big Three” Allied leaders (the Soviet Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom)

Zones of influence .. sound familiar! (US China Russia AI)