The many-faceted monster. The first part of a review at the New Criterion–pity about the book under review (see final para of quote):

Stalin: his own avatar

by Gary Saul Morson

On Stalin’s Library: A Dictator and His Books by Geoffrey Roberts [website here].

When the novelist Mikhail Sholokhov, who later won the Nobel Prize for literature, had trouble getting the third part of The Quiet Don approved for publication, he appealed to Maxim Gorky, then the supreme authority in Soviet literary affairs. Gorky invited him to his mansion, which had been a gift from Stalin to lure Gorky home from self-imposed exile. When Sholokhov arrived, he discovered that Gorky had company: Stalin himself.

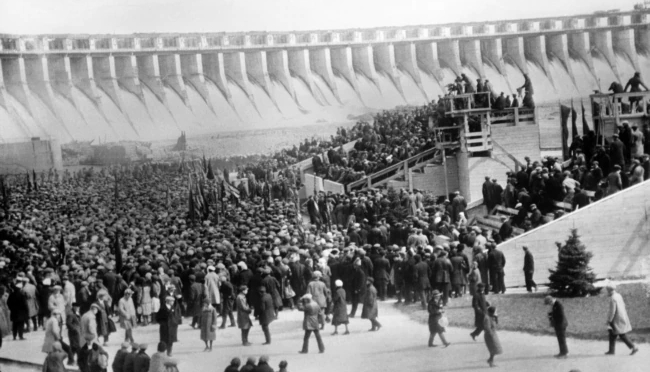

Stalin interrogated Sholokhov about ideologically problematic passages but agreed to the book’s publication on condition that Sholokhov also write a novel glorifying the Soviet collectivization of agriculture. Still more important, he gave Sholokhov a piece of paper explaining how to contact Stalin’s personal secretary, Aleksandr Poskrebyshev, and providing the number of his direct phone line.

Sholokhov’s collectivization novel also ran into trouble with officials too scared of its descriptions of Soviet ruthlessness. Dialing the sacred phone number, the novelist reached Poskrebyshev, who summoned him to a meeting with the vozhd’ (meaning “leader,” a term reserved for Stalin alone). Stalin spent three nights reading the manuscript. When Sholokhov arrived, he found, in addition to Stalin, Lev Mekhilis, the editor of the Communist Party newspaper Pravda; Sergo Ordzhonokidze, who was in charge of the economy; and Kliment Voroshilov, People’s Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs. Stalin approved the novel’s publication but “suggested” a new title.

Could one imagine a president of the United States deeming a novel so important that he would spend three days reading it and give his verdict in the presence of officials in charge of the economy and the army [emphasis added]? But in Russia literature is more important than anywhere else. The poet Osip Mandelstam famously remarked that only in Russia are poems important enough for people to be shot for them.

Even if an American president should deem a novel to be that significant, would he trust his own unaided literary judgment, as Stalin evidently trusted his? Americans usually presume that Stalin, as a mass murderer, must have been a semi-literate thug, as if intellectuals are somehow less capable of brutality. At best, they figure that Stalin, as his enemy Trotsky asserted, was a consummate intellectual mediocrity. In fact, Stalin was not only highly intelligent but also supremely well-read [emphasis added]. When the Soviet archives were opened after the fall of the USSR, it turned out that Stalin had accumulated a personal library of twenty-five thousand volumes. He had selected the books himself and even devised his own classification system for his personal librarian to follow. In over four hundred volumes he left extensive pometki, marginal notes. What was in that library? What did those notes say?

After the Party leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin in his 1956 “Secret Speech,” most of Stalin’s books were dispersed to various libraries—over the strenuous objections, it should be added, of his daughter, Svetlana, who claimed her father’s collection as her own. But the four hundred annotated books found their way into the Stalin lichnyi fond, or personal archive.

At the end of his riveting book Inside the Stalin Archives (2008) [2009 review here before peak Putin], Jonathan Brent describes the thrill of discovering these volumes. As the editorial director of Yale University Press, Brent was editing sixteen volumes of important documents from the (briefly open) Soviet archives. Having inquired about Stalin’s library on an earlier visit, he had no idea what he would find in Fond (“file”) 588, Opus 3, the designation for books and manuscripts discovered in Stalin’s personal library after his death. “I had not realized what an avid and comprehensive reader Stalin was,” Brent recalled, but the archive soon revealed to him something even more interesting: Stalin “saw the nation as a set of ideas as much as a set of economic or material facts. As I looked at page after page of Stalin’s corrections, annotations, and commentary,” Brent explained,

I realized that while he professed a worldview set radically against metaphysics and Kantian idealism, Stalin was an idealist in the sense that he believed completely in the primacy of ideas. This represents a radical . . . reorientation and revision of Marx’s philosophy and is the key to understanding Stalin’s threat to “mercilessly destroy anyone who, by his deeds or his thoughts—yes, by his thoughts—threatens the unity of the socialist state.”

Brent was right: Stalin was a man of ideas, to the point where he thought that by changing the ideas to which people are exposed he could redesign human nature itself [emphasis added]. The Bolshevik leader Nikolai Bukharin, his onetime ally and later victim, put the point memorably:

“If we examine each individual in his development, we shall find that at bottom he is filled with [nothing but] the influences of his environment, as the skin of a sausage is filled with sausage-meat. . . . The individual himself is a collection of concentrated social influences, united in a small unit,”

and, for unwavering Bolsheviks, nothing more.

At a famous meeting with writers held in Gorky’s apartment in 1932, Stalin explained how they should view their efforts:

“There are different products: artillery, automobiles, machines. You also produce “commodities,” “works,” ”products.” Very important things. Interesting things. . . . You [writers] are engineers of human souls. . . . Production of souls is more important than the production of tanks. . . . That is why I propose a toast to writers, to the engineers of human souls [emphasis added]”

No wonder that Stalin took such a keen interest in literature and ideas. Svetlana pointed out that in her father’s Kremlin apartment “there was no room for pictures on the walls—they were lined with books.” Stalin’s adopted son Artem Sergeev recalled that at every encounter his father asked him what he had been reading and what he thought about it. The son of the secret police chief Lavrenty Beria claimed that when Stalin visited someone from his inner circle, “he went to the man’s library and even opened the books to check whether they had been read.” Although he was always ordering books, Stalin borrowed from others as well. The poet Demyan Bedny was foolish enough to complain that he hated to lend his books to Stalin because they were returned covered with greasy fingermarks. That was the last Bedny saw of his luxurious apartment.

It is hardly surprising that Stalin read and reread Machiavelli’s The Prince. Neither is it strange that he knew well the works of his Bolshevik rivals Trotsky, Bukharin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev, or that he underlined key passages in Hitler’s Mein Kampf. But he also read a lot of Russian and world literature, apparently cherishing Pushkin as well as satirists and social critics including Gogol, Saltykov-Shchedrin, and Zola.

I expected to learn a great deal from the first comprehensive account of Stalin’s annotations, Stalin’s Library, by Geoffrey Roberts.1 A professor emeritus at University College Cork…

Alas, this book offers no significant discoveries, intimate or otherwise. It meanders pointlessly from topic to topic unrelated…